Will Oldham

CH: I think of your work as literature and for me listening to Palace and Bonnie Prince Billy is more like reading or thinking. There’s something sinister and clear and pastoral and funny in your music that alludes to a larger inaccessible body of work. How have you managed to carry that weight so lightly in sound while making it so grounded and deep through language? Do you think about this balance?

WO: Cara sometimes I can't take it; sometimes I can't stay ahead of everything rolling hard up against me. Today was one of those days. If the weight were addressed weightily, though, I'm sure that I would break. Treating the music--the writing of it, the performing of it, the participation in its existence in every way-- as if it were something in between a life-preserver and a utopian world where all contradictions are created equal and all forces work towards the fulfillment of our being...treating the music like that, and at the same time like there is a crew of editors and producers waiting to count the laughs, or add the laugh track... BALANCE!

CH: When you are singing what are you imagining?

WO: It depends on the song. Songs with long open deliberate passages that are difficult to sing...during such songs the imagination goes wild, because imagery and action is good for the mind when the throat is looking for hand- and foot-holds. Often times the songs deliver images, interactions, memories, hopes; I am caught off guard far more often than not. I found that when I began to anticipate an image, that image would shy away.

CH: There is another world behind the stripped down sound you produce. I think it’s only partly carried in your lyrics. What is your process when you are putting these things (sound and voice and language) together?

WO: Right. I'm glad that you say that; I feel like I try to minimize the interface in the hope that the worlds on either side of the song have the space then to expand. The process? I don't know how to describe it.

CH: What is your work day like?

WO: Every day is a work day, and most days are different.

CH: What are the books that that have influenced you? What are you currently reading?

WO: Right now I am reading THE LONG SHIPS by Frank Bengtsson and it is influencing me. Fiction writers over the past decade or two: Charles Willeford, Knut Hamsun, Mohammed Mrabet. A recent book that was important to me was I LOVED YOU FOR YOUR VOICE by Selim Nassib. I really got a lot out of Greg Noll's autobiography, DA BULL. Also Dave Eggers'S ZEITOUN and WHAT IS THE WHAT, and Tracy Kidder's last couple of books, among the more popular titles. One book that was big for me was Chip Brown's GOOD MORNING MIDNIGHT. I just read a good Gershwin bio by Walter Rimler, and an interesting book about Billie Holiday called WITH BILLIE. I liked Frank Capra's autobiography too. Olaf Stapledon's SIRIUS, and, to a lesser extent, ODD JOHN. I also just read Somerset Maugham's THE NARROW CORNER. I like his writing, and that of Graham Greene. I like Robert Louis Stevenson very much. I know my reading tends heavily towards male writers. Hugh Nissenson, Ian MacMillan (who wrote stories and novels about modern Hawaii). A friend gave me Marilyn Robinson's GILEAD but I haven't found myself able to start it yet.

I like to read some every day. When I am touring it is next to impossible to do so.

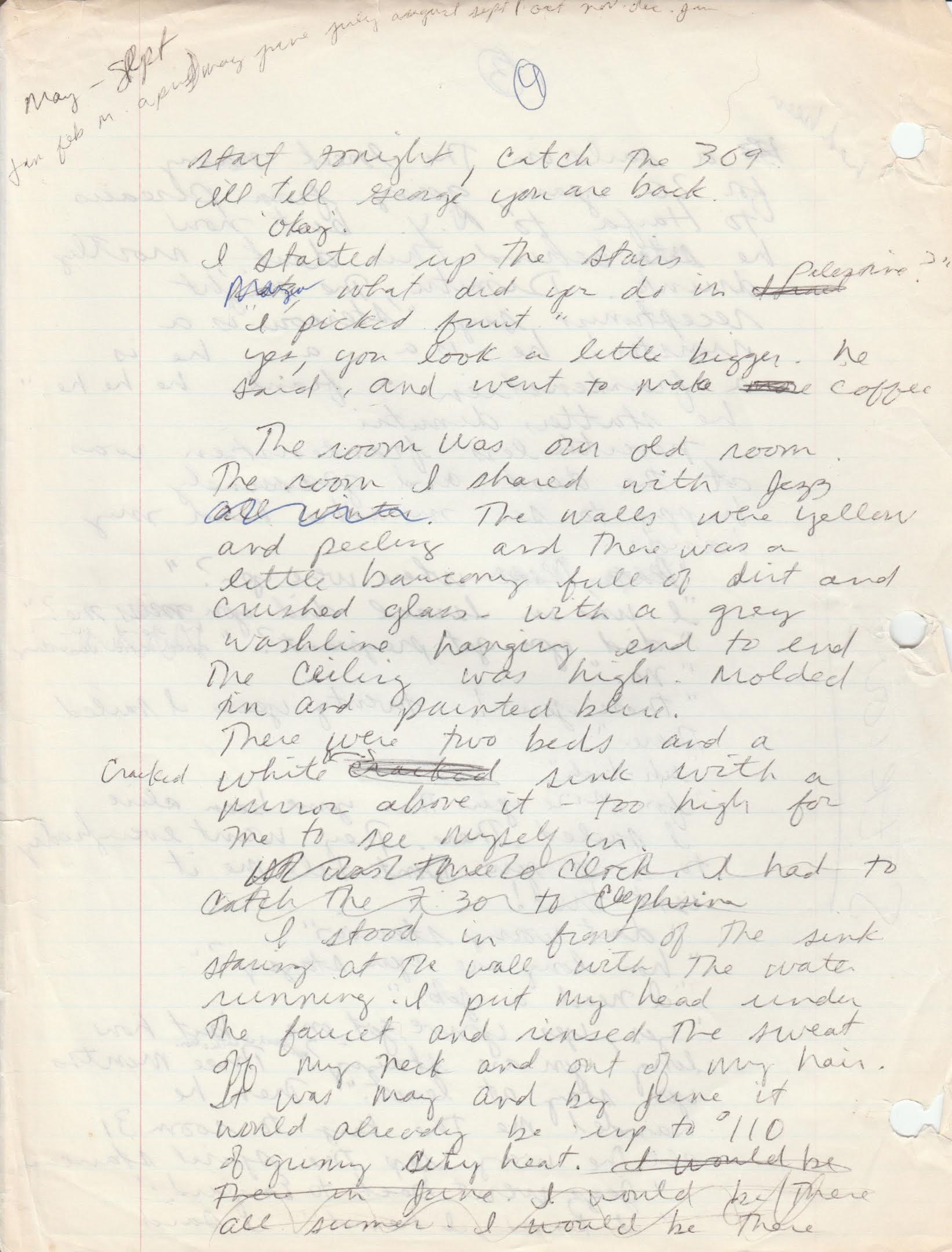

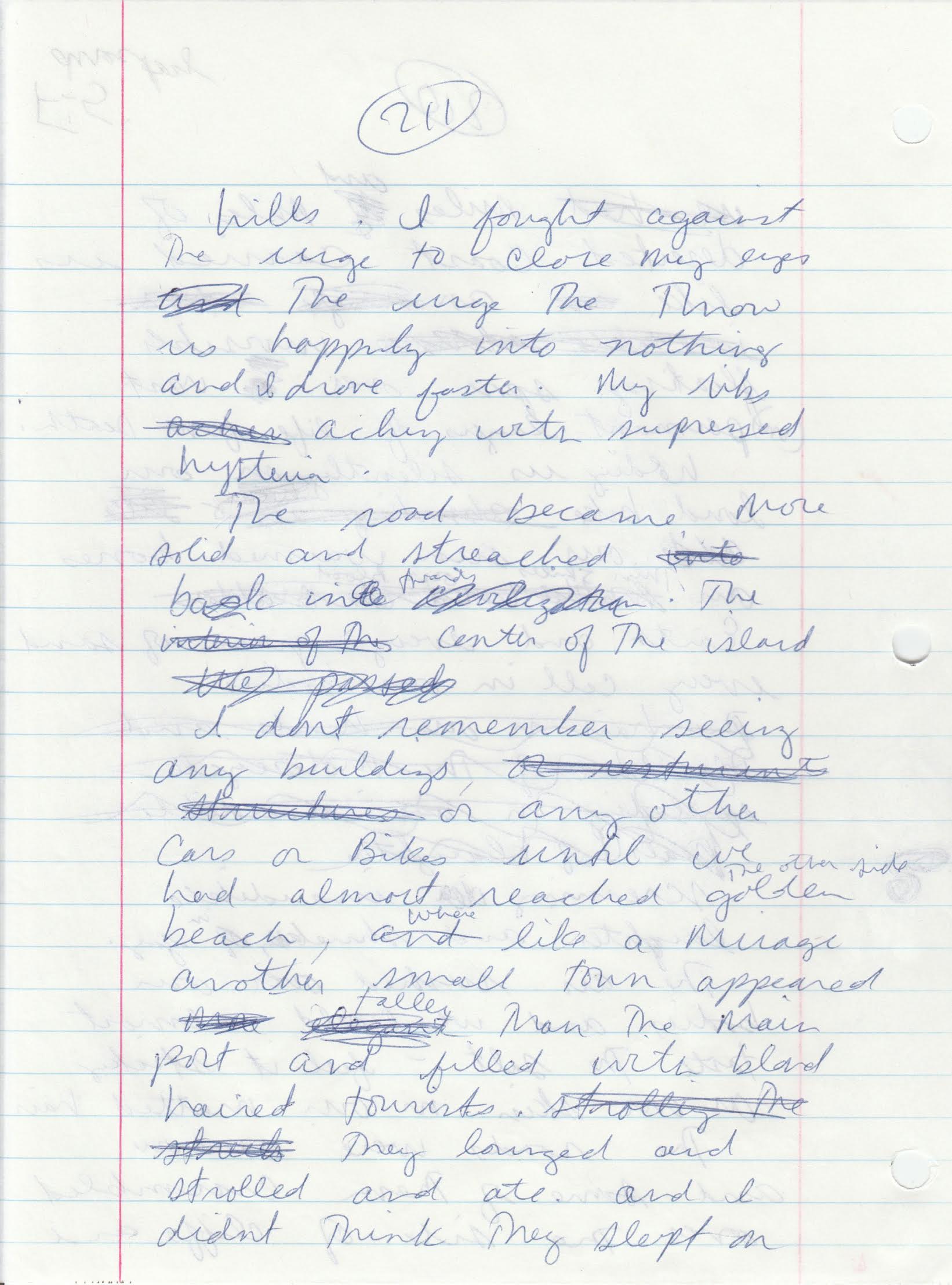

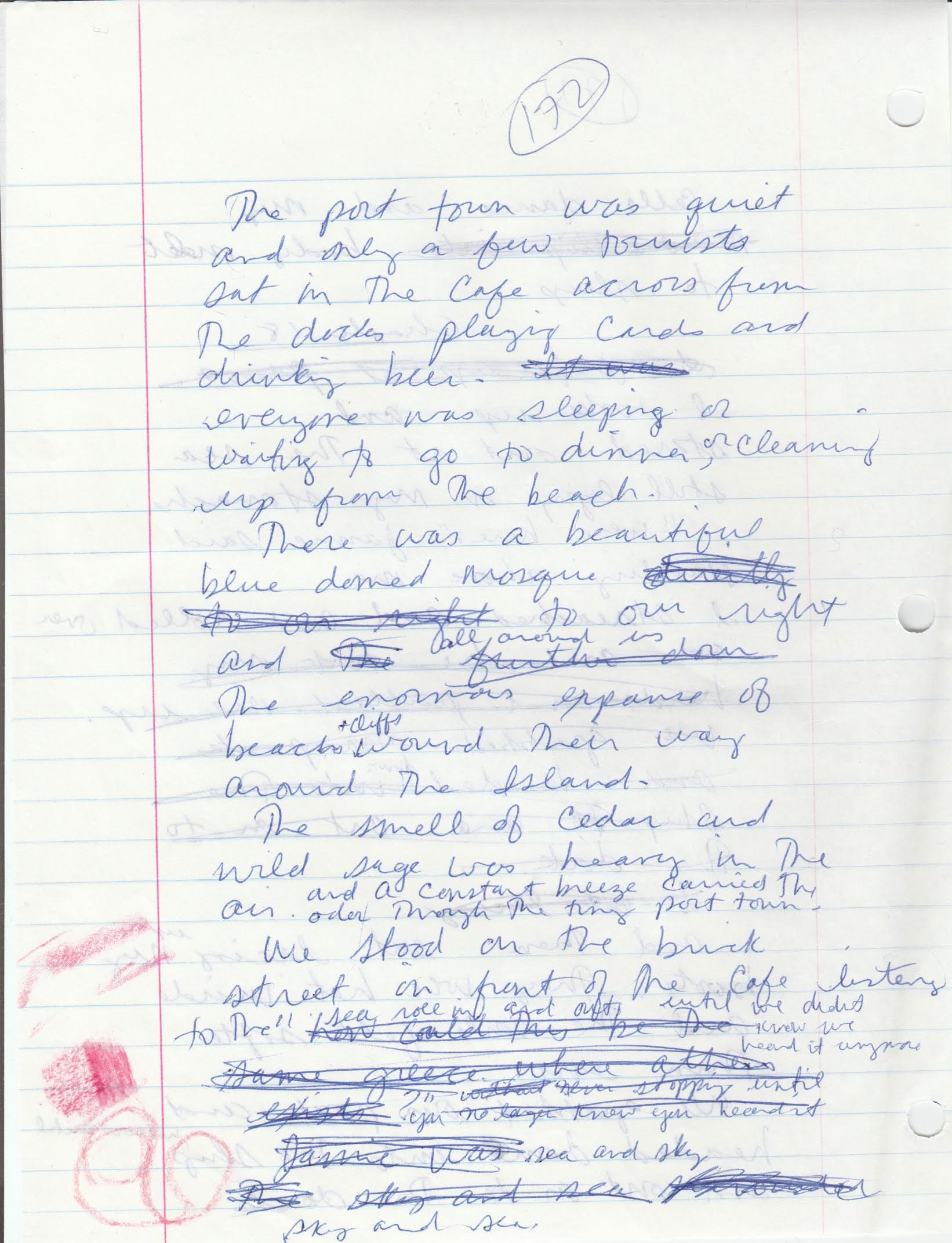

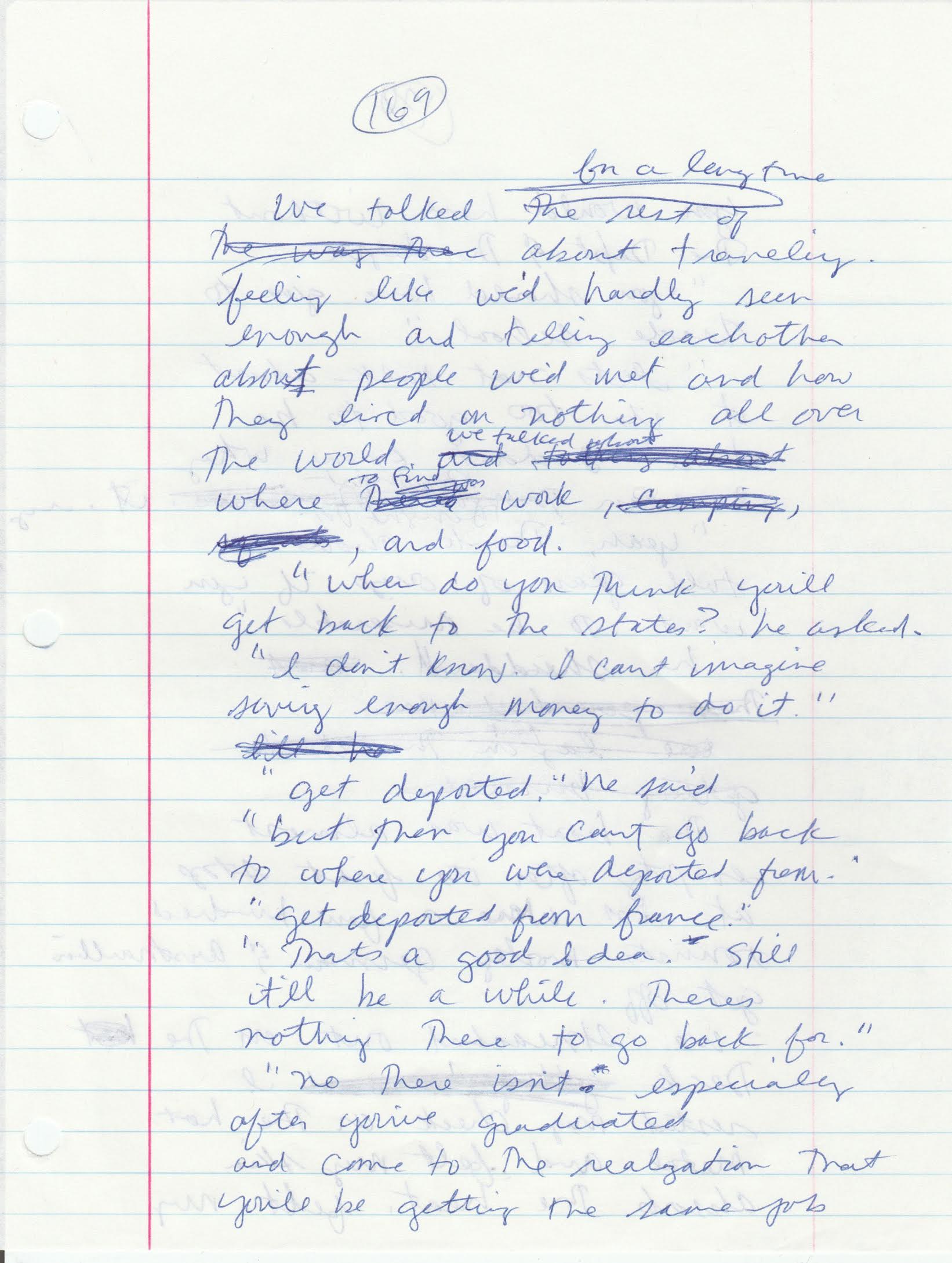

Writing happens, more often than not; I look at a stack of papers or at a notebook and realize that writing has been happening for months without my being aware of it.

Paper

I began folding cranes and frogs when I was nine. My best friend taught me how and we spent an entire summer filling our rooms with paper animals.

Origami replaced a fascination with melting army men and throwing them off the garage roof, an activity of which I thought I could never tire.

But then I read the book Sadako and the Thousand Cranes, a novel about a little girl exposed to radiation during Hiroshima. Sadako believed in a legend that said if you folded one thousand paper cranes you would get your heart’s desire, and her heart’s desire was peace. She died after folding six hundred cranes and I took it upon myself to fold the rest. But I couldn’t stop after four hundred.

My new skill also coincided with the theater release of the movie Blade Runner, in which one of the bounty hunters folds origami and speaks very little. In my mind at nine, leaving a folded fish somewhere could be an warning to someone, an unspoken threat or a clue.

Origami might have seemed like a more feminine hobby than burning army men and flinging them out into a field, but to me the two acts were essentially the same, were born from the same anxieties and desires, the same nascent sense of my place in the world as someone who would likely grow up to be a woman.

I might have had to live in an era where a former B movie star with a nuclear death wish was president, but I could silently affirm to myself, with a square of paper, that a better day was coming. I could straighten the beak and pull out the wings to ready a paper bird for flight, and no one would know that I was seeing helicopter gunships being blown out of the sky by little girls standing on the ground.

LOU

I met Lou Reed twelve years ago before I lived in Manhattan. I’d come to the city by bus from a small gray town unreachable by trains to give a reading at Bluestockings and was staying with my brother on the Lower East Side. When I checked the paper to see if I'd been listed I saw that Lou Reed had a book signing the same day for his collection of photographs of New York. It was a few hours before mine.

I can barely articulate my relationship to the music of The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed.

Andy’s Chest was the lullaby I sang to my son every night when he was a baby. A song from an album that was for years one of the only things I owned besides a change of clothes. There was no way I would miss getting his book and giving him mine.

Like anyone who's heard stories about his life, I was prepared for Lou to be a prick in person. I carried his book and my book of short stories up to the table where he sat and before I could say anything he asked, “What’s that?”

“A book I wrote. I brought it for you.”

He took it, read the epigraph and smiled “Well are you gonna sign for me?”

"Sure." We signed books for eachother. “I have a reading tonight in the East Village,” I told him. “Maybe you can make it.”

“I’ll try,” he lied. Then asked “Where’d you come from?”

“Trumansburg.” I said.

“What?” he nearly spit. “Trumansburg? Where the HELL is Tru-mans-burg?”

“Upstate.”

“Well you gotta get out of there. Take this as a sign."

"I do."

“Alright,” he said.

"Alright."